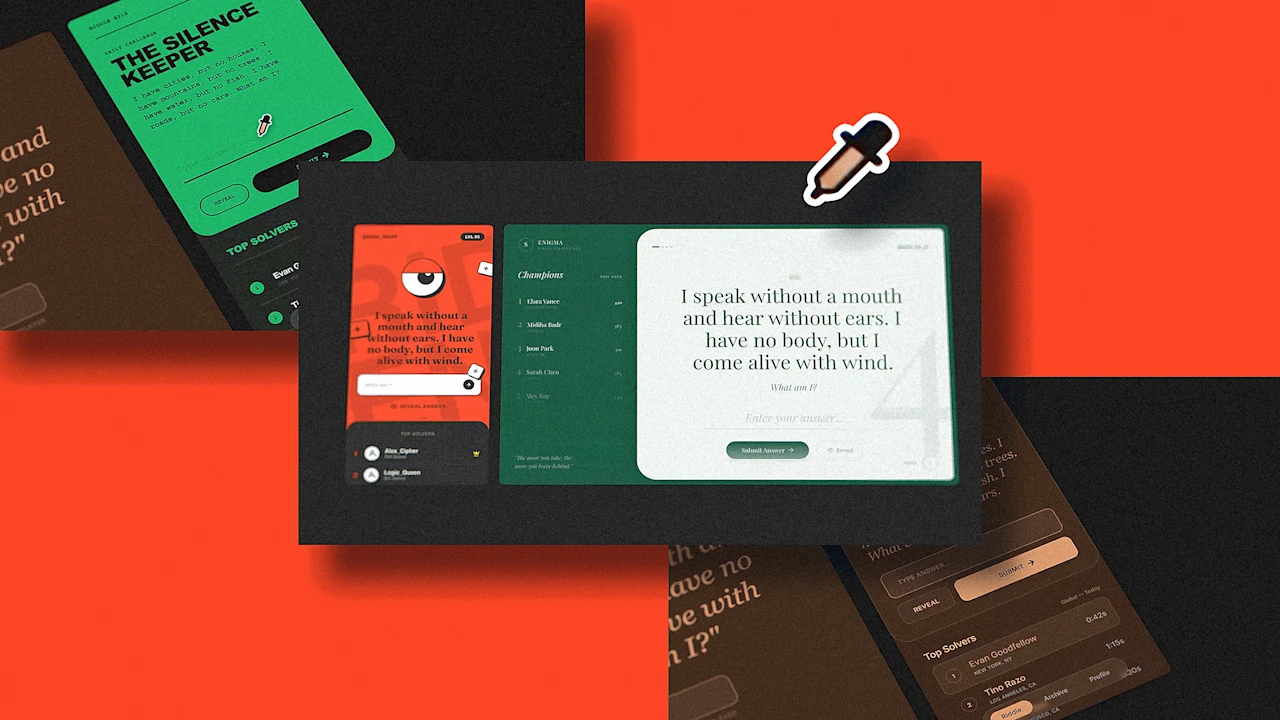

Variant, a generative design tool that promises endless UI exploration, recently introduced a feature most creative people and designers have used for decades: the eyedropper. In Variant, the tool picks vibes: It lets you click on one AI-generated interface and inject its aesthetic DNA—typography, spatial relationships, and color palettes—into another. After so much hype around “vibecoding” and its text-based imprecision, seeing a familiar, direct manipulation tool applied to generative AI feels great.

The new AI modality takes a nice step to close the gap between the impenetrable ways of large language model black boxes and the tools designers actually use with their eyes and hands. Adopting a universally understood tool to control AI in any way other than words is exactly the kind of innovation the sector needs now.

It’s just too bad that Variant itself is the vessel for it. The tool’s underlying AI engine suffers from a distinct lack of differentiation. Everything it makes looks flat and same-y, so the new style absorb-and-drop tool is not really that useful. Yes, the transformed UI changes, but the results already looked very similar anyway (except for the color palettes).

That said, the implementation is cute. When you click on a previously generated UI, the eyedropper animates the design as it is sucking its soul. You then move the eyedropper, click on another generated UI, and the new style spills over it, rearranging it to match the source. It’s a satisfying bit of UI theater, an illusion broken by the fact that you have to wait a little to see the results, as the AI works it all out.

The problem is the little variance in Variant. You can’t “eyedrop” a bitmap image or a Figma project and tell the AI, “make this new app UI look like this.” Currently, Variant’s eyedropper feels like trying to paint in Photoshop when your palette only contains five shades of beige.

A for effort

That’s too bad, considering the eyedropper is one of the most resilient and powerful metaphors in computing history. The concept dates back to SuperPaint in 1973, which introduced the ability to sample hue values from a digital canvas. While MacPaint popularized digital painting tools in 1984, it was Adobe Photoshop 1.0 in 1990 that locked the eyedropper icon as the standard for color sampling.

Then, in 1996, Adobe Illustrator 6.0 evolved the tool into a style thief. It allowed designers to absorb entire sets of attributes—stroke weights, fill patterns, and effects—and inject them into other objects. Now Variant is effectively trying to take this to its UI design arsenal. The difference is that Adobe’s tools offered precision. You knew exactly what you were getting. With Variant, you are making a visual suggestion to a probabilistic engine and hoping for the best.

But it is a good change that highlights why we need more tools like this eyedropper and fewer text prompts. Unlike the latest generation of multi-modal video generative AIs, the lack of precision in vibecoding tools is unnerving to me. It reminds me of an exercise I did in communication design class, back in college: A professor made us play a game where one student built a shape with Tangram pieces and had to verbally describe to a partner how to reproduce it with another Tangram set. It was impossible to match it.

We are humans, orders of magnitude better semantic engines than any AI, and even we fail at describing visuals with words. We need interfaces that allow for direct, exact manipulation, not just crossing fingers and hoping for the best. Variant’s eyedropper shows us the way. Generative AI tool makers, more of this, please. Stop forcing designers to talk to the machine, and let us show what we want.