When the British designer Fred Rigby released his first furniture collection in 2021, he knew from the outset he would prioritize a U.S. audience—a bigger market with more sales opportunities, he says. Rigby designs and manufactures elegantly crafted furniture in the Oxfordshire countryside, and has built strong relationships with interior designer clients in cities like New York, L.A. and Miami.

For a few years, things went according to plan. As his studio grew, 60–70% of sales came from the U.S. market. Then in 2025, all of that changed. “We had a healthy-looking pipeline, but when the tariffs came in, we just saw more and more projects disappear,” says Rigby.

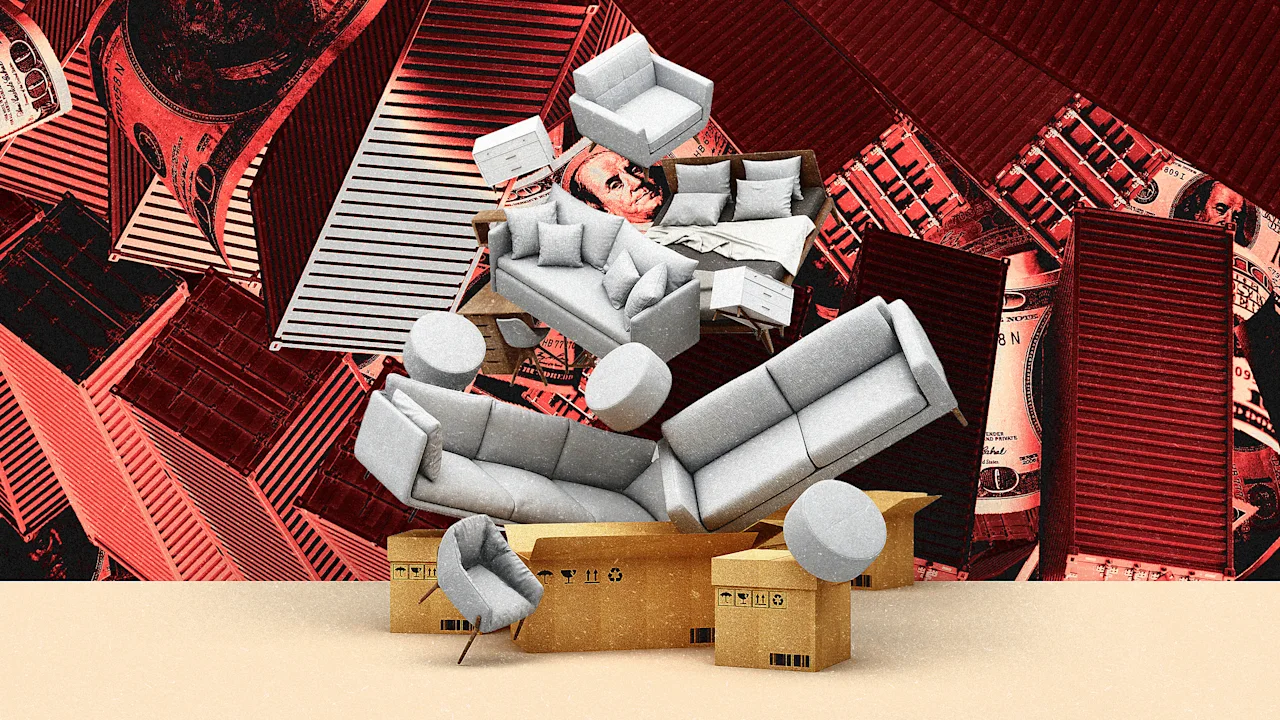

Since October 14, upholstered furniture imported to the U.S.—such as sofas and armchairs—has been subject to a 25% tariff, which is due to rise to 30% on January 1, 2026. In reality, trade deals with specific countries affect this final number. For instance, tariffs on all imports from EU countries are capped at 15%; for the U.K., it’s 10%; for Brazil, it’s 50%. Different elements of a furniture item can even be subject to varying tariffs based on their country of origin.

These changes and uncertainties have rattled the furniture world, including foreign furniture makers with significant U.S. markets like Rigby and U.S.-based interior designers sourcing global furniture. Even domestic furniture brands, who often rely on international materials, are taking a hit. Delaware-headquartered American Signature, parent company of furnishings retailers American Signature Furniture and Value City, filed for bankruptcy in November, citing the economic impacts of tariffs.