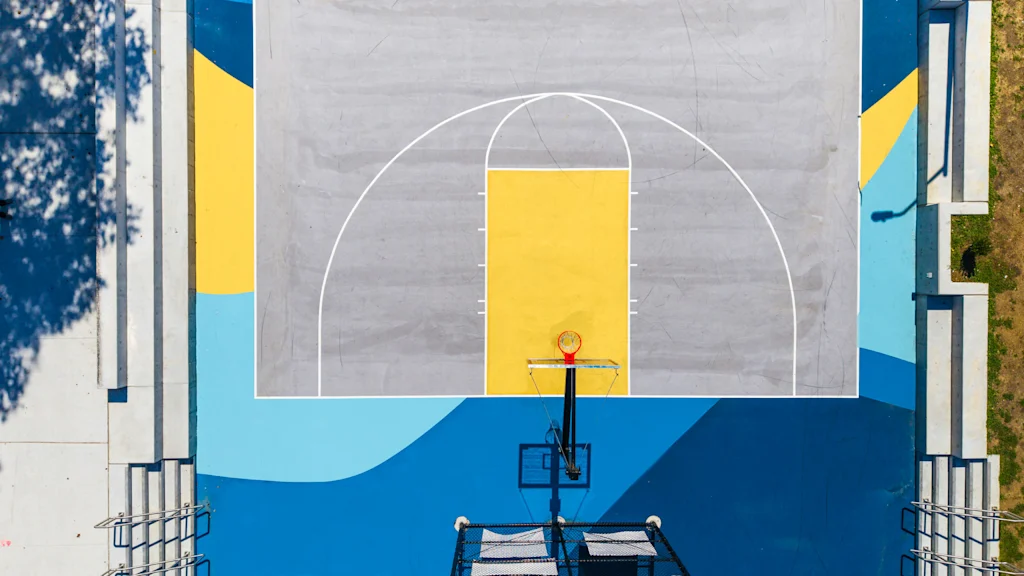

They look like ordinary basketball courts. But two new courts built next to public housing in New York City double as flood prevention.

In a sudden flash flood—when the city’s aging sewer system can easily become overwhelmed and streets can fill with water—the sunken basketball courts act like retention basins. The design can hold as much as 330,000 gallons, with the court’s lowest areas filling like a pool and additional water stored in bioretention cells beneath the surface.

The project “becomes like a sponge, which basically holds the water as much as it can,” says Runit Chhaya, principal at Grain Collective, a landscape architecture firm that worked on the design with city agencies, local residents, engineers from Hazen and Sawyer, and the urban planning firm Marc Wouters Studios. “It helps in not putting stress on the city storm system during a flood event.”

The redesign is part of a larger program that began in 2017, when the New York City Department of Environmental Protection drew inspiration from the way that low-lying cities like Copenhagen were dealing with “cloudbursts” of extreme rain.

Climate change is making heavy storms more likely because warmer air holds more moisture, loading clouds with extra water. It’s an even bigger challenge in cities like New York that are covered in pavement and that have combined sewer systems, meaning a single system handles both household sewage and stormwater.

As the city looked for ways to capture stormwater, public housing sites presented an opportunity. “NYCHA is unique in having large pieces of property within very dense neighborhoods that provide the opportunity to mitigate stormwater overflows in a way that most properties do not,” says Siobhan Watson, vice president of sustainability at the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA).

There was also an opportunity to improve public space. The design team worked closely with NYCHA residents, emphasizing that the project wasn’t just about climate change. “It’s very hard to go to these communities and just start talking about climate change and flood protection because they are thinking about basic needs and we are talking about infrastructure they didn’t even ask for,” says Chhaya. “So you kind of change the story—and it’s an honest story that, hey, it’s actually a win-win situation. You’re going to get an upgraded amenity.”

At South Jamaica Houses, an apartment complex in a low-lying, flood-prone neighborhood in Queens, the project replaced two older basketball courts with the new sunken design. The courts are now surrounded by steps so spectators can watch a game or casually hang out. The space is also designed to be used for other purposes, like a summer movie night or farmers market.

During storms, rain from nearby streets is channeled through pipes into bioretention areas beneath the basketball courts. The courts, which are roughly three feet deep, also can hold up to a foot of water in areas and then slowly release it. Most of the stored water seeps underground in the 48 hours after a storm. If the subsurface storage is full, a valve allows the rest of the water to overflow to the sewer only when there’s capacity.

The inspiration came from similar designs in Europe, including a “watersquare” in Rotterdam that functions as public space most of the time but captures water in heavy storms. The projects are an investment—the first system at South Jamaica Houses cost around $5 million—but could help prevent more costly damage.

When planning first began, the city was thinking about long-term resilience. “At the time, we had not really experienced these kinds of extreme rains that we’ve seen over the past few years,” says Watson. “And over the course of time as this project has been developed, the context has totally changed.” The city has now seen storms like Hurricane Ida, in 2021, where extreme, sudden rain caused severe flooding and killed 11 people living in basement apartments. Ida showed the danger is real and urgent, underscoring the need for projects like the new courts.

Now, New York City is moving forward with more of the infrastructure at other public housing around the city. At a complex called Jefferson Houses, a new playground under construction uses permeable pavers to channel rainwater into underground storage tanks. Another basketball court is set to begin construction at Clinton Houses, and other projects are in the design phase now at four other sites.

The final deadline for Fast Company’s World Changing Ideas Awards is Friday, December 12, at 11:59 p.m. PT. Apply today.