During President Donald Trump’s first administration, he left hundreds of government designers, across half a dozen or more agencies, to do their jobs.

But that changed the second time around, in January 2025, when a reelected Trump wasted no time turning the official White House website into his personal blog, deleting resources for topics ranging from reproductive rights to the contributions of Navajo code talkers in World War II.

Then in February, Trump took a sledgehammer to the digital infrastructure of the U.S. when he enlisted Elon Musk to lead the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). In a vast cost-cutting initiative, DOGE destroyed half a dozen of the government’s digital design agencies. Hundreds of talented people recruited over decades lost their jobs, according to the best estimates of former government designers. The teams who launched everything from healthcare.gov to that handy site for ordering free COVID-19 tests were decimated.

Now the design of America has been entrusted to one person overseeing the skeleton crews that remain. In August, Trump appointed Joe Gebbia as the country’s first chief design officer.

Gebbia is in charge of the America by Design initiative, and under Trump’s order has opened the National Design Studio “to improve how Americans experience their government—online, in person, and the spaces in between.”

“We’ll be guided by the best user experience,” Gebbia tells Fast Company. “It doesn’t matter who you voted for or what side of the spectrum you associate with or believe in. Everyone can agree that government websites are underwhelming, and they would enjoy a better design, better user experience, and faster page load times.”

It’s an attractive promise, made by a man who, in many ways, appears to be a great fit for the job. Gebbia is the billionaire design cofounder of Airbnb. He graduated from the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design. He’s a fast-moving, private-sector creator of one of the most popular digital services of the past 20 years. His CV is exactly right for America by Design’s mission, which is to make chores like applying for your citizenship or filing taxes “something you actually look forward to.” It’s a Silicon Valley mantra that’s overused and overly optimistic, but it’s also fundamentally hard to argue with.

Yet in speaking to a dozen government designers and experts for this piece—serving across the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations—it’s clear that Gebbia’s biggest challenge isn’t making the drudgery of navigating government services delightful or even easy. It’s navigating the inherent tension of doing so in an administration that’s actively undermining basic human rights.

“You can’t talk about people losing their Medicare and have a slick website,” says Paula Scher, partner at the celebrated graphic design firm Pentagram. “It just doesn’t go.”

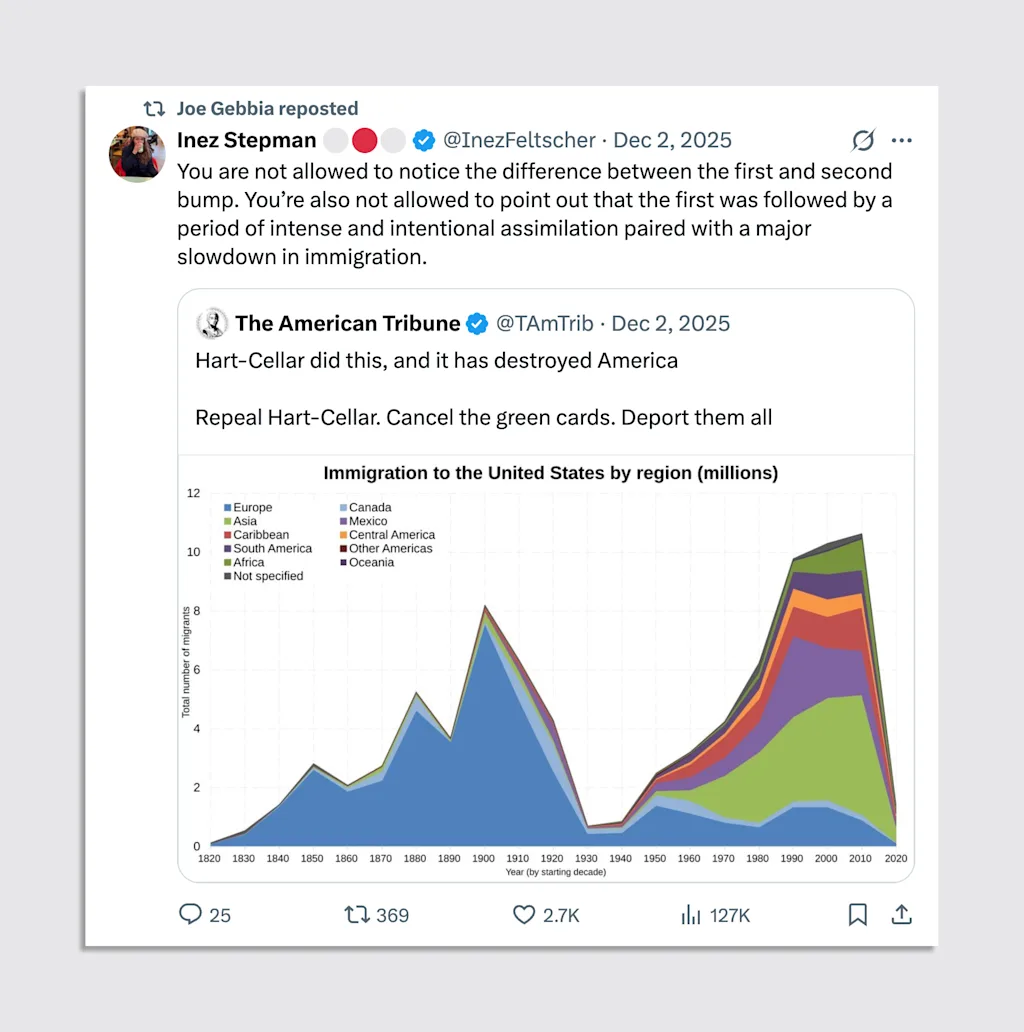

Gebbia, who promised his fortune to the Giving Pledge in 2016, has recently positioned himself as a MAGA Republican who challenges vaccinations and has promoted the idea on X that immigrants should lose their green cards. Still, his ideologically opposed peers continue to believe that the power of design triumphs over all. That includes his Airbnb cofounder Brian Chesky, who defends Gebbia’s position and the good he can do as a pure digital practitioner.

“As you think about it, the way that most people interface the U.S. government is through an app or a website,” says Chesky. “If those apps or websites were easier, so you could visit a national park, pay your taxes, get your benefits or Veterans Affairs stuff, that’s a good thing. It’s not inherently political.”

But the work has been political. Months into his appointment, Gebbia’s promise to fix the UX of American services is far from realized. Instead, the Trump administration has traded several flawed but human-centered government design agencies for a red-pilled web 2.0 propaganda czar.

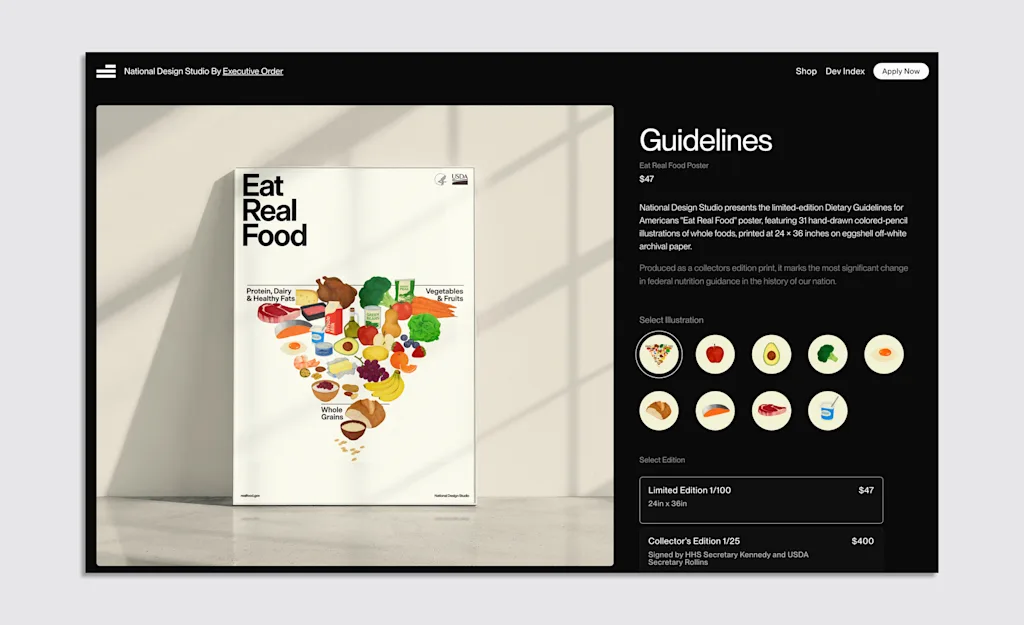

In his time as chief design officer, Gebbia has launched half a dozen websites that don’t so much repair the online experience of the U.S. government as promote Trump’s projects like Kickstarter campaigns reskinned in vintage Apple typefaces. The high-gloss websites for Trump Accounts and the Genesis Mission might give the appearance of an Apple Store-like experience, but Gebbia’s designs have also gone live with hundreds of accessibility violations.

At best, the work has been cringe (have you seen the Trump gold card?). At worst, it has distracted from an erasure of human rights, as trans resources and even practical words like disability have been purged from government websites this year.

Still, many of the people I spoke with exhibited a certain envy for the position Gebbia finds himself in. It’s an unprecedented moment in which design has been elevated to the top of the country, backed by an executive order to get things done. With the assistance of Musk, Trump razed America’s design services as we know them, leaving nothing in Gebbia’s way to build anew.

“He’s inheriting the blank check kind of environment . . . [so] according to the laws of physics, he should be able to get a lot done,” says Mikey Dickerson, founding administrator of the United States Digital Service (USDS). “But if the things that he’s allowed to do, or the things that he wants to do, are harmful, then he’ll be able to do a lot of harm in a really short amount of time.”

Redesigning the government

In January 2025, Josh Kim was working for the State Department through a private contract agency, building the department’s updated digital accessibility standards. A dashboard tracked all the pages the government needed to modernize, from passport applications to adoption pages, to ensure everyone could access them.

Following Trump’s reelection, the administration sent out a memorandum to end DEIA (diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility) projects—with a mandate to cancel all related private contracts. Kim says he was told by management to erase every mention of “disability” and “accessibility” from his work immediately, before his firm was audited or asked to do so.

“There was definitely this wave of fear that the consultancies were kind of like, ‘Oh shit, they’re going to cancel our contracts if we mentioned any of these things,’” Kim says. His experience was far from isolated. In the early days of the Trump administration, similar erasure happened across government design agencies—with much of the work documented on GitHub.

It wasn’t just words that were lost in this purge. One week after the memorandum, the Veteran’s Affairs site relabeled “Accessibility at the VA”—a webpage that allows disabled veterans to flag interface issues—to “508 Compliance (accessibility).” The code refers to the law for IT accessibility, but sounds like a plot twist from Stranger Things.

While the page still exists, it’s the kind of update that obfuscates information to many of the people who need it. A third of veterans rely on the VA for disability benefits, and the update fundamentally damages the feedback loop between the government and the people it serves.

It’s but one example of how government design services readied themselves for an invasion, and an invasion they got. In February 2025, Musk’s DOGE team arrived in D.C. and began cleaning house. By March, hundreds of government designers were gone as the most powerful design agencies inside the government were functionally dismantled.

The (sometimes necessary) pangs of democracy

Modernizing UX has been a big initiative of the government since President Barack Obama launched the Office of Digital Strategy in 2009 to connect the White House to digital channels. He then established a Presidential Fellows program in 2012 to recruit a new wave of technologists to public service. To date, 250 people have joined for 12- to 24-month tours of duty, including product leads on the Nest thermostat, Nike+ FuelBand, and talents who had worked at Disney.

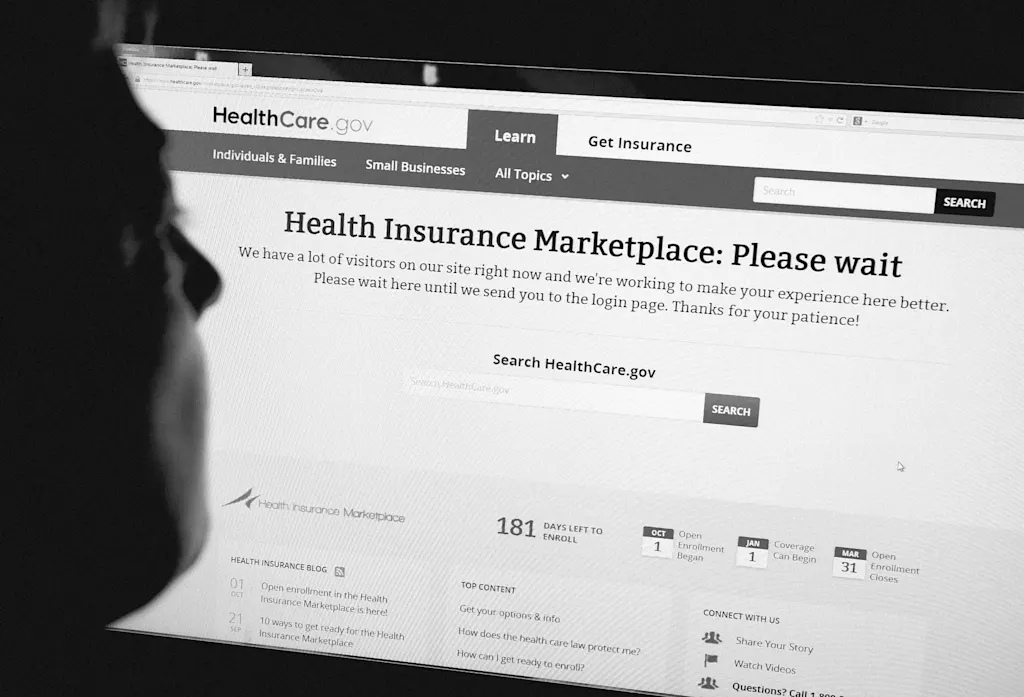

Even with this added technological firepower, government services still needed more day-to-day design support. That arrived in 2014, when two critical internal agencies—the USDS and 18F—were created out of one of the biggest digital failures in U.S. history, the botched launch of healthcare.gov.

On the day healthcare.gov launched in 2013, 250,000 people tried to purchase health insurance, only to find a website that was unusable, with dozens of problems ranging from account registration failure to frequent crashes. It was so bad that only six people were able to sign up for healthcare coverage on the day of launch.

Mikey Dickerson recalls arriving from Google to found what would become USDS. His first job of fixing healthcare.gov was done in just two months, from October to December 2013.

“I mean, that was approximately a miracle, honestly,” he says, noting that entrenched government employees got a wake-up call from a disgraced Obama administration. “This was a very rare case where doing nothing was going to have consequences, because doing nothing meant that this very visible policy failure wiped out all of their careers.”

Both the USDS and 18F doubled down on longer-term, private-sector recruiting. These two organizations alone recruited 18 people from Google, along with talents from Amazon, Facebook, Twitter, and the popular Silicon Valley incubator Y Combinator. Nikki Lee, a former product manager at 18F, created the stylus interaction used by Windows 10 and 11. The recruiting effort was enough to catch the attention of OpenAI cofounder Sam Altman in 2015, who called the talent grab “on par with the best Silicon Valley startups.”

It’s a recent history that Gebbia has entirely ignored when promising to build a “dream team” of the “best talent of our era—the best designers, the best software engineers”—as if that’s a new concept for the government. (A government initiative called Tech Force launched in December 2025 to address the government’s loss of talent under DOGE.)

When I ask Gebbia about his thoughts on the USDS and 18F—and whether he thought these groups were overrated and needed to be rebuilt—he shrugs off the topic as before his time.

“Without knowing too much about the groups you mentioned, I do know that the air cover and the urgency around design is in a place it’s [never] been before,” he says.

Whether Gebbia acknowledges them or not, USDS and 18F offer precedent for America by Design. The agencies were designed to work across different parts of government. USDS was a crisis agency focused on triage. 18F was an internal design consultancy built for longer-term digital solutions. Combined, they had an approximately 350 head count at their peak with a combined budget of around $40 million (though the USDS received a $200 million grant in 2022 to invest in tasks like modernizing Social Security IT and getting low-income Americans online).

It’s easy to frame the progress across a constellation of government design services as too slow, too bureaucratic, and, most of all, too unusable. No one recognized these issues more than the government designers working to address them.

“It is not like a corporate setting. It is not like a nonprofit setting. It is not like higher ed,” says Rachael Dietkus, the first social worker hired at USDS, who describes her first two years of working for the government as very difficult. “The learning curve is absolutely massive. It can be very confusing. There is a lot of hierarchy.”

These agencies weren’t perfect, but they represented progress. Yes, they still had to operate around entrenched government employees who weren’t always motivated to move fast. But the bigger obstacle was often legislation the government had already decided upon.

“Sixty percent of why the design of things sucks is because the policy sucks,” Dickerson says. “If you wanted a SNAP [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program] application to be really simple, like, you could absolutely do it. You could do it the same way we did the [free] COVID test.”

When the government sent out free COVID-19 tests in 2021, policymakers decided that they could be available to anyone who requested them. “We’re not going to go around checking whether you have the money. If you wanted to do that exact same program but you want to do it means tested, where I have to prove that I can’t afford my own COVID tests? Well, guess what? Now you’ve got an application process that is nine months long. And we’ll have an appeal, and an appeal to the appeals,” Dickerson says.

Her point mirrors what I heard from many government designers: You cannot have simplicity in government services in the face of eligibility verification, legal due process, and the ability to apply for services without a computer. That’s ultimately why many digital services aren’t as simple as the public would like.

Clare Martorana, who was appointed chief information officer under President Joe Biden, left the role alongside that administration. She updated legacy systems that had been infiltrated by China and Russia, launched IRS direct file with 18F and others to sidestep the TurboTax ecosystem, and responded to the pandemic with the aforementioned COVID-19 test site (developed alongside the U.S. Postal Service by a handful of designers) that simply made tests appear at your door, no questions asked.

But a lot of Martorana’s job was simply keeping projects moving, and to circumvent old, dated policies that perpetually impeded her work. “I received numerous emails from [managers] asking me, ‘There’s a guy here in our team that won’t move forward with this thing because of this 1995 e-government [policy]. And can you please write me back so I can share that, from your vantage, sitting under the president, your interpretation is that this is no longer the primary regulatory thing that someone should focus on?”’ she recalls. “But you know, we over-indexed in adding new rules and regulations and never did the housework of cleaning our closets.”

As an optimist who began in the private sector, she believed DOGE could do a lot of good in removing this “calcified bureaucracy.” Instead of hyperfocusing on trying to run these inefficient structures more efficiently by cutting head count, she believed Musk would bring in “blue sky thinking.”

Instead of fixing broken systems, Musk’s team could have simply built a better, cheaper version of things that existed. These systems could have duplicated old public services—albeit through modern technology that proved out its own benefits and cost savings—without breaking anything.

“That’s what I thought Elon Musk was going to bring to the party,” Martorana laments. “I don’t think he built SpaceX by mimicking NASA.”

No doubt, government design systems were too bureaucratic and needed a shake-up to move faster. But DOGE’s approach did nothing to build resilience or retain the government’s design progress of the last decade.

“I’m not ashamed to say, like, ‘Yes, I absolutely covet the blank check that they were handed.’ If I had that in 2014, I could have gotten a lot of shit done,” says Dickerson. “But if Donald Trump’s administration were to say, ‘You can be the new Elon Musk,’ I’d still pass on that job. Because what they’re trying to do is destroy everything.”

Lobbying for the job

Of course, one designer wanted that job. And he lobbied hard for it.

Gebbia joined DOGE in February 2025, two months before Musk’s departure from the organization. His government work under that team began with his takeover of a multiyear initiative to digitize the paper-based retirement system of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). He claims that in six months, his team evaluated the work, threw out all the code, and launched a new system that’s operational more than a year ahead of schedule.

Ashleigh Axios, founder of the consultancy Public Servants, served as creative director and digital strategist under Obama and later worked on OPM digitization under her former firm, Coforma. She cautions, “As with many long-running federal modernization efforts, it’s common for new administrations to spotlight progress that began under earlier contracts.”

In any case, those efforts garnered the attention of several Trump Cabinet members: Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, Attorney General Pam Bondi, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Secretary of State Marco Rubio, and Kelly Loeffler of the Small Business Administration. Gebbia met with them to discuss the work.

“It was really these conversations across the government where I started to dream a little bit,” he says. “I started to think, Wow, there is actually a real demand here for this. I started to think . . . The government’s kind of like a design desert, and everyone’s reaching out asking for a glass of water. I know how to find . . . a cold glass of water for them.”

But Gebbia says he wasn’t simply offered a job. Rather, the entire pitch process was more like fundraising in his Silicon Valley days. In May, he began a three-month lobbying campaign to create the National Design Studio. He started with a traditional Keynote presentation, before learning that the government preferred big foam-core boards. He ended up carrying 20 of them at a time.

“I remember the first day, going to a Secret Service checkpoint, and I put [the pile] through the X-ray machine. And the whole thing was a mess. And I’m like, Oh man, I gotta make a case for these things,” he recalls. “I custom built this foam-core case—just this big white case. I’m kind of walking around D.C., walking around the White House compound.”

After meeting with enough agencies and Cabinet members, honing his pitch along the way, he eventually got an audience with Trump’s chief of staff, Susie Wiles. Gebbia calls that meeting “one of the best pitches of my life.” A week later, he had the ear of the president, who greenlit the vision. As of August, Gebbia was operating as chief design officer, reporting directly to Wiles.

“It [had] to be a presidential initiative for this to work at scale. And that was really one of the only ways that I was going to stick around to do this,” Gebbia says. “The whole architecture of this . . . was done in such a way that we’re one foot away from the president.”

Gebbia wastes his blank slate

When Gebbia first took the job, he connected with Scher of Pentagram and discussed the position, noting his excitement for the possibilities to get a lot done.

“[Trump’s] an autocrat. That’s the best corporate client you can have,” says Scher. “Just one opinion, and you’ve sold the damn thing.”

The problem is that Gebbia’s governmental work thus far has been shallow at best, and fundamentally hypocritical at worst. While he’s promised to improve usability to core government services that serve a majority of Americans, his most visible projects have been little more than advertising campaigns for the Trump administration. These efforts include sites like trumprx.com, trumpaccounts.gov, and trumpcard.gov.

“The gold card’s embarrassing. The typeface is hackneyed. If I were judging a design show, that’s what I’d say about it,” Scher says, examining the websites before offering a more nuanced criticism. “But it isn’t terrible. . . . There’s nothing wrong with it particularly as a piece of design except I think it’s incredibly inappropriate.”

Should Americans be excited about a 12 Days of Design advent calendar, published as their healthcare premiums have quadrupled from Trump’s elimination of Obamacare subsidies? Should the Americans who’ve lost food security—as the Trump administration refused to release earmarked funds to provide food stamps during the government shutdown in 2025—be excited about the new food pyramid telling them how to eat?

These projects read as promotion of Gebbia’s glossy vision for government design, rather than an American government resource, with little to no actual service attached to it.

“[Trump] wants to make it look like a business. It’s not a business,” Scher says. “The government is a place that creates laws and programs for society—it’s not selling shit.”

Silicon Valley sells innovation by default. Overzealous promises and jokey 404 errors are just part of the vibe of move fast, break things culture. But designers who worked at design agencies across the government call out how that sort of easy breezy Valley perspective misses the point of public service—that you are often supporting people in the worst moments of their lives, and there’s a level of decorum you need to exhibit in consolation.

“My grandfather passed away a couple years back. We filed VA forms to have him buried in a VA facility. That’s a whole process,” says Axios. “I don’t expect that to be delightful. I’m grieving.”

Gebbia’s Valley-inspired work is evident in other sites, too. His design for genesis.energy.gov—a new federal AI research initiative—borrows the sans serifs and black backdrops of modern Apple ads. Viewed in full, it lands as any stereotypical technology site, full of servers and glowy sci-fi nonsense (though the presentation was enough for Reddit cofounder Alexis Ohanian to proclaim “this is awesome”).

Perhaps if the Trump administration hadn’t gutted America’s university system, reduced National Institutes of Health research grants, and ostracized its pipeline of overseas talent that’s driven a century of innovation in our country, a government AI program might feel like progress. Instead, let’s call this what it is: not much more than a Squarespace page glossing over an unprecedented rollback of federal funding for scientific research across the U.S.

But Gebbia’s page for the National Design Studio is the most unintentionally apropos. The logo features a black-and-white flag with three stripes and no stars: an attempt at modernism that lands closer to looking like a country in mourning.

These criticisms are largely superficial. But so is the work. Gebbia has referenced solving real UX pain points for Americans. We’ve yet to see him do more with front-end design than posting bold mission statements and offering a few data collection forms.

When I flag these early projects as simple, Gebbia offers a fair retort. “Are we going to reimagine a hardcore corner of the government in eight weeks with a brand-new team?” he asks. “[Or] are we going to pick some quick wins and learn how to work together and ship some things so that we understand what’s involved with deploying great code?”

Still, these randomly branded, stand-alone sites further bifurcate an already confused system of government services. Critics I spoke to point out that even with pared-back designs, they feature sloppy code, large download sizes, and fail reasonable accessibility standards. (Gebbia claims accessibility has been addressed. Anna Cook, an accessibility expert and designer at Microsoft, notes some fixes have been made, but “most of the core issues identified earlier remain unchanged.”)

These sites also introduce more risk of malicious parties spoofing government resources. Most of all, they are inherently more concerned with how America looks than how it works.

When I point out that much of his work seems to prioritize storytelling over functionality, Gebbia replies with a touch of exasperation. “I don’t know, should it be boring? I guess it’s sort of the bar at the moment,” he says. “You go to a government website, you kind of feel like you’re on a government website. I don’t know, can it be a little more magic? Because Americans deserve more than that.”

Veneer, however, is easy for any designer. It’s untangling government services that’s hard. “Unless you’re actually delivering services to the public, you’re [not] simplifying the digital experience,” says Martorana.

Before leaving with Biden, Martorana wanted to simplify the cacophony of digital services with a visual system that would unite all government websites under USA.gov. While the project ended with the Biden administration, the proposed brand featured a logo from Pentagram, with a stoic U and A, but a stylish, energetic S in the middle. Its simple brilliance was that it could then be paired with every seal used across the government, coalescing many government services into a more ideal entity. And it didn’t simply ignore the existing network of 450 agencies that provide ongoing services to the American public.

Martorana laments the feature creep in which the government added more and more websites, even before Gebbia, when in fact the top nine government websites represent 160 million visits every month. Those sites should be getting the most immediate attention, she argues. And getting people to the right one, faster, could be the best thing we can do immediately.

Gebbia shares that his team is, indeed, currently charting out a strategy for updating some of the largest government websites, and is entering the research phase now. That work could hold significant promise, and any single one of those projects would dwarf the National Design Studio’s efforts thus far. But he’s choosing to keep the work secretive, in what appears to be the setup for a larger, more dramatic reveal than we typically see in publicly funded government projects.

“What you’ve seen so far are short stories, and we started on the novels,” Gebbia says. “Let’s just say that.”

The great undoing

Gebbia believes deeply in the power of design to better the life of everyone. He has promised to fund the teachings of his design idols Ray and Charles Eames in perpetuity, the midcentury designers who first inspired him to take up design, and brought good taste to America through mass-produced furniture.

Yet he does not share their ideals. According to Eames biographer Pat Kirkham, the Eames “definitely had liberal politics” as Democratic donors who quietly backed many of their Hollywood friends during McCarthy’s Red Scare. Ray Eames went so far as to buy corsages for children whose parents had been jailed for their leftist beliefs.

The duo did contribute to the Federal Design Improvement Program under President Richard Nixon—an initiative that Gebbia has cited as a precedent for America by Design. But if Trump had asked the Eames to help the government today, or take on a chief design officer role for his administration? “My sense is that the Eames might have said, ‘No thanks,’” Kirkham says. “I just think that [Trump’s politics] would have appalled them, really.”

Gebbia remains an excellent storyteller who has mastered the art of the promise. But when asked questions on specifics—for example, could his own hypothetical Gebbia version of the VA site use the word disability instead of “section 508”—he dismisses the point.

“I haven’t been involved in this. I can’t speak to it,” he says.

Or when asked if he’d rebuild IRS.gov after the Trump administration pulled the working platform from 25 states, he replies, “Before my time.”

Gebbia says his unwillingness to engage in the politics of design is in service of design itself. “I think that at the end of the day, our focus is just [to] make the best user experience,” he says.

Yet this is one of the most dangerous narratives coming from Gebbia and some of his Silicon Valley peers. These new government technologists believe that the politics at play right now do not really matter, and that a strong design sense—a core understanding of UX—can repair the loss of government resources.

“It makes me very proud of our country for a moment. . . . Having this role, and it being an executive order, that the president has ID’d as important is probably the best way to signal to all people [working on] these experiences there should be intentionality,” says Katie Dill, who led experience design in the early days of Airbnb and is currently head of design at Stripe. “At its core, design is intentionality.”

If design is the manifestation of intent, then good design can be born only from good intent. Gebbia’s intent as a designer is directly tied to that of the administration for which he works—one that has been systematically dismantling the rights of the people it is meant to serve. Given the administration’s current priorities, it seems unlikely for Gebbia to execute positive design on a wide scale.

For now, many designers are eyeing Gebbia’s position with a mix of fear, envy, and patience, waiting for the political tables to turn so they can continue their work again.

“Silicon Valley’s really getting trend-based. Everyone’s swinging to Trump. But there’s a greater than 50% chance that the next president will be a Democrat. That’s just how it goes,” says Chesky. “I do think the country has needed the chief design officer. I think it’s a good post. And I hope when a Democrat is president—whenever that is—they keep the position.”